By Howard J. Bennett, MD

Asthma is a common childhood problem. In a primary care setting, most children with asthma have a mild, intermittent condition that resolves by middle school. Unfortunately, many children are not diagnosed with asthma in a timely fashion. Instead, they get antibiotics for recurrent “bronchitis” or they cough for weeks every time they get a cold and no one considers that asthma may be the underlying reason for the cough.

When I take a family history, parents often tell me they don’t have asthma even though doctors have given them asthma inhalers in the past. I suspect the prescribing doctor didn’t mention asthma because the diagnosis carries a negative connotation, and he didn’t want to “worry them.”

My perspective is different. If parents are educated about asthma and have the right tools at their disposal, they will do a better job managing their child’s symptoms.

What is asthma?

The medical term for asthma is reactive airway disease. In some ways, this is a better name because it helps explain what’s happening in the respiratory tract. When someone has asthma, his bronchial airways are “reactive,” which means they constrict and become swollen in response to certain triggers.

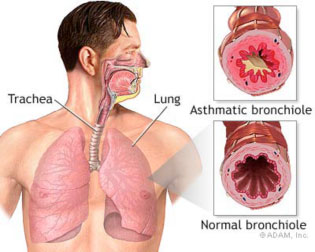

One way to visualize a bronchial tube is to imagine a garden hose that’s cut in half. The hose corresponds to the wall of the bronchial tube. The inside of the hose corresponds to the inside of the bronchial tube, also called the lumen. The wall of the bronchial tube contains bands of muscle.

Three things happen during an asthma attack. First, muscles in the wall of the bronchial tube constrict making the lumen smaller. Second, the inside lining of the bronchial tube produces excess mucus. Third, the lining of the bronchial tube gets swollen from inflammation. Each of these actions make the inside of the tube smaller, which makes it more difficult to breathe just like twisting a hose would reduce the water flow from the nozzle.

What triggers asthma?

Asthma can be triggered by different things, and some people have more than one trigger.

- colds and the flu

- irritants (outdoor pollution as well as smoking, chemical fumes, etc.)

- allergies to trees, grass, pets, dust, mold, etc.

- exercise

What are the symptoms of asthma?

Children with asthma experience one or more of the following symptoms:

- coughing

- wheezing (a whistling sound that comes from the chest)

- chest ache or tightness

- difficulty breathing

- exercise intolerance

What are the signs of worsening respiratory distress in children?

The following signs indicate that a child is having respiratory distress:

- rapid breathing

- heaving of the abdomen with breathing

- the skin between the ribs or above the collar bones retracts or “pulls in” with each breath (The medical term for this is retractions.)

- making a grunting sound with expiration

- flaring of the nostrils with each breath

- rapid heart rate

How is asthma diagnosed?

There is no one test that diagnoses asthma the same way a throat culture is used to diagnose strep. Older children can get skin tests and lung function tests at an allergist’s office, but most pediatricians make the diagnosis clinically. If a child presents with shortness of breath and wheezing that responds to asthma medication, there’s a high likelihood the underlying diagnosis is asthma.

It’s more common, however, for a child to present with a cold and a mild wheeze without respiratory distress. Sometimes the wheeze is audible, but many times it can only be heard with a stethoscope. Children 3 years and older will usually take a deep breath when asked, and this makes it easier to hear wheezing. Younger children not only can’t do this, but frequently cry during office visits, which makes it more difficult to assess lung sounds.

It’s not uncommon for asthma to present with a persistent cough rather than a wheeze. It some cases, I hear a subtle wheeze when the child coughs. This too, helps support the diagnosis. However, if I see a child who coughs for 2 to 3 weeks every time he gets a cold, I become suspicious of something called “cough variant asthma” even if I don’t hear a wheeze. The best way to confirm this diagnosis is to treat future coughs with asthma medication and see if it changes the child’s previous pattern of coughing with colds.

How is asthma treated?

Asthma treatment targets the three changes that occur within the child’s airways. One group of medication reverses constriction (spasm) of the muscles in the wall of the bronchial tubes. The other group reduces the inflammation (swelling and excess mucus production) on the inside of the bronchial tubes and reduces the sensitivity to environmental triggers.

Bronchodilators

Bronchodilators are referred to as rescue medications because they relax spasm of the muscles in the wall of the bronchial tubes. Bronchodilators are usually taken by inhalation, either with plug-in machines called nebulizers or handheld devices called metered dose inhalers (MDIs).

Bronchodilators can be given every 4 to 6 hours if needed, but most kids take them three times a day. For older children, this means they take it before school, once they get home in the afternoon and before bed. Bronchodilators work quickly, usually within 10 to 15 minutes of the dose.

The most common bronchodilator is called albuterol. In comes as a generic and under a number of trade names such as Ventolin, Proventil and ProAir.

One of the side effects of albuterol is that some kids get jittery or “hyper” after taking the medication. If this happens to your child, he might do better with a special type of albuterol that goes by the trade name, Xopenex.

Some asthma medication pairs a long-acting bronchodilator with a steroid. They are used primarily in children with persistent or exercise induced asthma. Two common brand names are Advair and Symbicort.

Steroids and Other Anti-Inflammatory Medication

Steroids reduce inflammation. If you’ve ever used hydrocortisone cream for an itchy rash, you were applying a topical steroid to reduce inflammation in the skin that caused the redness and itch.

The steroids used in asthma can be given orally, by inhalation or intravenously. Steroids don’t work as quickly as bronchodilators and are typically taken twice a day. Most children with asthma take inhaled steroids, but a child may need a few days of oral steroids if he was in distress when the symptoms began. Hospitalized children usually get steroids intravenously.

Montelukast is an oral medication that works to reduce the inflammation associated with asthma. It’s taken once a day and is usually added to someone’s regimen to reduce the need for daily steroids.

How long should a child take asthma medicine?

The answer to this question depends on the type of asthma a child has and what his triggers are. Doctors have specific guidelines that determine whether a child has intermittent or persistent asthma. If a child has asthma with colds 4 or 5 times a year, he has intermittent asthma. If a child has lots of environmental allergies that require daily asthma medication, he has persistent asthma.

Most children have mild, intermittent asthma that is triggered by viral infections. In that case, they should take their medication as long as they have the virus plus another 4 to 5 days to prevent a relapse of asthma symptoms. However, if asthma symptoms are triggered by tree pollen and it’s the middle of March, he will probably need medication for 2 to 3 months until the tree allergy season ends.

Some children have persistent asthma with no clear trigger. In this case, they may need to take medication everyday to keep their symptoms under control.

How to take medication effectively

Although it’s relatively easy to drink a liquid or swallow a pill, taking inhaled medication requires a bit more skill.

Using a nebulizer

A nebulizer uses compressed air to turn a liquid into tiny droplets that can be inhaled. The advantage of a nebulizer is that it requires less cooperation from the child. As a result, it’s useful with infants and toddlers or older children who are too sick to use other devices.

Nebulizers work like an ultrasonic humidifier. Liquid medication is poured into a chamber and the device is turned on. The nebulizer creates a mist that the child breathes in over a 5 to 10 minute period. Some children wear a mask that fits over their nose and mouth. Others won’t tolerate a mask in which case parents aim the mist toward their nose and mouth.

Some children are frightened by the noise generated by the nebulizer. You may be able to lessen the noise by putting the nebulizer on the floor or by turning on a video to distract the child.

Using a metered dose inhaler

A metered dose inhaler (MDI) is a handheld device that consists of a metal canister that fits in a plastic “holster.” When the canister is pushed downwards, a fine mist shoots out of the device.

The main advantage of an MDI is that it’s much faster than a nebulizer. That being said, it is harder to use correctly. The mist comes out of the canister very fast, and a child needs to inhale at the right time to get the medicine into his lungs. For this reason, children less than 10 should use spacers that make the timing of the dose less critical.

Here are some suggestions for using an MDI with or without a spacer.

- Shake the inhaler well before using it.

- Have your child sit up straight or stand when he uses the device.

- Make sure there is nothing in your child’s mouth or the device before each use.

- Have your child breathe in and out deeply one or two times before triggering the device. (I tell kids this is a stretch breath.)

- Your child should hold his breath for 5 seconds after slowly and deeply inhaling the medication. If he can’t hold his breath, he should breathe in and out of the spacer 4 times for each puff of the device.

- Children may have difficulty activating the MDI correctly, so parents should be the ones to trigger the device.

- If your child is taking an inhaled steroid, he should rinse his mouth with water when he’s done.

- Some children complain about a bad taste after using MDIs. You may be able to gain their cooperation by letting them eat a salty snack before using the inhaler or by giving them a small treat after.

Nowadays, most MDIs have counters on the device so you know when the medication has run out. Make sure to pay attention to this number and the expiration date before giving the medication to your child.

Exercise induced asthma (EIA)

Asthma that’s triggered by exercise is considered when a child has shortness of breath and coughing in association with vigorous exercise. The child may be fine during PE or when he’s playing with friends, but during soccer games or other strenuous activities, his exercise tolerance is reduced.

A child can also be short of breath if he’s out of shape, so this needs to be considered when making a diagnosis of EIA. Most children with EIA cough when they’re having trouble breathing, whereas out of shape children usually do not cough.

Most children with EIA use a bronchodilator 15 to 30 minutes before exercise. Others need an inhaled steroid, a long-acting bronchodilator or montelukast in addition to a bronchodilator to control their EIA.

What is the connection between asthma and bronchiolitis?

RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) is a common infection in the first two years of life. Although some children with RSV only develop symptoms of a cold, others get a lower respiratory tract infection called bronchiolitis. As the name implies, bronchiolitis affects the bronchiole tubes. The lining of the tubes get swollen and produce excess mucus like an asthma attack. However, the constriction (spasm) of the muscles in the wall of the tubes does not occur with bronchiolitis.

Most children with bronchiolitis are mildly sick for a week or so with a runny nose, fever, cough and wheeze. Some children, especially infants, may develop respiratory distress and need to be hospitalized for a few days.

Research has shown that infants who get bronchiolitis are more likely to have asthma symptoms for the next few years. It’s unknown if RSV triggers the asthma or if children who are predisposed to asthma are more prone to bronchiolitis.

Video Links

The following videos help illustrate techniques for inhaled asthma medication:

- Nebulizer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U1aU0UbQUYQ

- Spacer with mask: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uGkbreu169Q

- Spacer without mask: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e6rAIxVnin4

- MDI without spacer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lx_e5nXfi5w

Conclusion

Asthma is a common childhood disorder that resolves in the majority of kids before puberty. If your child wheezes, has a lingering cough with most colds or has a persistent cough during allergy season, he may have asthma. If you notice these symptoms, even if they’re mild, discuss them with your doctor. And always remember this central fact: The more informed you are about asthma, the better you can take care of your family.

© 2016 Howard J. Bennett. All Rights Reserved.

For more articles and other information, please visit Dr. B’s website at http://www.howardjbennett.com